The Jazz Butcher's Indie Pop Genesis

Very long ago, in the mists of the early 1980s, “indie” and “pop” had not yet conjoined to become a compound word. There was the pop that inhabited the charts, and there was everything else.But the pop that was created and distributed at the independent level was indeed unlike pop as most people know it, both then and now. Transparently low-budget and conspicuously disheveled, it didn’t sound like punk, but it couldn’t have existed without punk’s ripping up of the musical rulebook and demolishing of the barriers to entry. It tended to be melodic but coarse, unaffiliated with recent technology (if the Top 10 was the sound of penthouses, this was the sound of a cement-walled cellar), and its lyrics usually made plain that these were people who were unafraid to flaunt their own intelligence and feelings.

In 1983, the Smiths would become the standard-bearers of U.K. indie-pop, bringing the (admittedly vague) notion of the genre to an audience of previously unimaginable size and scope. But before them there were the little-known but trailblazing likes of Orange Juice, The Monochrome Set, Marine Girls, and, almost simultaneous to the Smiths, The Jazz Butcher.

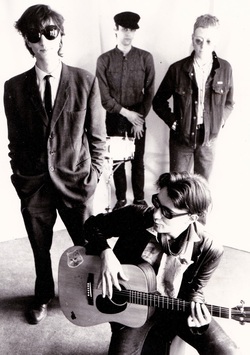

The Jazz Butcher, from the town of Northampton, in England’s Midlands, was the brainchild of fellow singer-guitarist-songwriters Pat Fish (aka “the Butcher”) and Max Eider. The purpose of the band, in Fish’s telling, was to “free my mind from the increasingly dank post-punk ghetto that it had been inhabiting.” When a friend lent him a compilation album of 1970s soul hits, he had a vision of a new way forward, and in response, wrote a song called “Partytime” that was a three-and-a-half-minute repudiation of post-punk’s sonic and verbal tendencies toward deadly seriousness. This was bright, wry, happy-to-be-alive music. It was, in its own skewed, understated way, pop.

Throughout the following three years, the Jazz Butcher made four albums for Glass Records, an independent label whose business structure—essentially, one man sitting in a room in London—belied the breadth of its achievements, also releasing classic left-of-center albums from the Pastels, Spacemen 3, Nikki Sudden, and many others. Those Butcher recordings have now been collected together on The Wasted Years, a four-CD box set accompanied by a booklet with a fantastically eloquent 5,000-word essay from Fish.

Above all else, The Wasted Years demonstrates that the Jazz Butcher seemingly existed to throw curveballs. The band’s very name served to confuse and mislead: Max Eider’s stunningly elegant six-string work aside (arguably, only Johnny Marr was a better guitarist at the time), there was nothing explicitly jazz about them. From debut long-player In Bath of Bacon onward, every disc is an exploding confetti bag of styles, moods, and textures, from the Velvet Underground-at-a-sock-hop velocity of “Jazz Butcher Theme,” to the aggressively, hilariously atonal “Caroline Wheeler’s Birthday Present,” to the conventional melodiousness and sentimentality of “Big Saturday” (the great, lost should-have-been indie number one). Their songs’ common denominator was Fish’s and Eider’s vocals, often delivered with the poker-faced poise of a genial game show host.

“We used to reply that we thought surprises were supposed to be a good thing,” says Fish. “A buyer is going to be stuck with your LP for at least a year before the next one comes out, so, come on, give them a little bit of something to chew on, no?

“The great liberating album for our generation was London Calling by the Clash,” he offers. “They broke out of the three-chord restrictions of their first album and the faintly dodgy chorus-metal of [second album] Give ’Em Enough Rope, and just played any kind of music they wanted to. At a time when the post-punk mob seemed to be removing more color, texture, and beauty from their music with every passing week, London Calling was a revelation, taking us back to reggae and soul and everything that was possible. From that day on, it was an article of Jazz Butcher faith that ‘punk’ meant playing whatever the hell you wanted.”

Following In Bath of Bacon’s very modest public reception—“It cost less than £500 to record; at the time, I had no idea that I would ever make another one,” says Fish—the following year saw the Jazz Butcher exceed everyone’s expectations, including their own. The band became a solidified unit with the addition of drummer Owen Jones and bassist David J, grateful to have found an artistic outlet that was the polar opposite of his recently deceased previous band, goth pioneers Bauhaus. Their 1984 album, A Scandal in Bohemia—made, like every subsequent release for Glass Records, with producer John A. Rivers, whose principal talent was making diminutive indie bands sound like they were playing in a canyon—was such a drastic progression from its predecessor that it seemed five years ahead of itself. It sold more than 20,000 copies.

“We found ourselves, rather to our surprise, in the middle of the music game in London at a golden moment where some of the principles of punk had actually become normal business practice,” says Fish. “It didn’t stay that way for long, but for a while there was a genuine feeling that the independent sector was ahead of the major labels. The level of ‘success’ we achieved certainly did surprise us. It completely astonished us. After a year or two, we could no longer cope with it. We were entirely unprepared, which manifests in all sorts of silly ways that you can’t possibly anticipate until you’ve been there. I wouldn’t have missed a second of it.”

A Scandal in Bohemia and its follow-up, the mini-album Sex and Travel (Fish’s personal favorite from this period), attracted enough attention that the Jazz Butcher soon signed on the dotted line with labels around the world, including in the U.S. and Canada. While other U.K. bands, who had received more acclaim and sold more records at home, made few inroads internationally, the Jazz Butcher became favorites of college radio audiences abroad. (Bloody Nonsense, a flawless 1986 compilation made exclusively for North America and Australia, has probably served as an introduction for more people than anything else the band did.)

“The West Coast of the American continent has always been the place where we’ve done the best business, all the way from Vancouver down to San Diego. Hell of a commute, mind,” says Fish. “We’ve also had regional success in Chicago, Toronto, New York, Hamburg, Valencia, Paris, London, Tokyo... ; all over the place, really; always at club/small theatre-level, and always economically viable.”

Having received what Fish in his box set notes as “the inspirational crash course in liberal education that is touring,” the band—now minus David J, who departed amicably to launch the soon-to-be chart-topping Love and Rockets with two of his former Bauhaus colleagues—returned to the studio to make “our greatest album ever.” Yet the resulting work, Distressed Gentlefolk (which followed very closely on the heels of Bloody Nonsense in 1986), is something of a misfire in Fish’s estimation, despite it remaining a fan favorite to this day. In retrospect, Fish says, there were several contributing factors: him and Eider going “in different directions” as songwriters, David J’s departure leaving an unfillable void, and “fatigue and liquor.” Although the album’s release was followed by a successful first tour of the U.S., Eider left soon after for a vastly underrated solo career. (His debut, The Best Kisser in the World, deserves a garlanded reissue of its own.)

This was far from the end of the Jazz Butcher, though. A reconfigured lineup left Glass and signed to the then-emergent Creation Records, where they remained until Fish retired the concept in the middle of the ’90s, their music seemingly too idiosyncratic to find its place in the culturally myopic Britpop years. But the band—variously featuring Eider, Jones, J, and other alumni—has been fitfully active again since the turn of the century. The Wasted Years is by far the greatest of several gestures that keep interest in the Jazz Butcher simmering. Fish views his Glass-era recordings as a memento of a very different time that nevertheless feels at home in the here-and-now.

“We never felt the urge to sound fashionable, which is probably why most of those old records still sound enjoyable today,” he says. “We were young and full of enthusiasm and weird, dogmatic ideas, and more than half the time we had no idea what we were doing. We were learning on the job and sometimes falling down in public. It beat the hell out of working in an office.”

—Michael White

The Wasted YearsFeaturing ‘Bath Of Bacon’, ‘A Scandal In Bohemia’, ‘Sex And Travel’ and ‘Distressed Gentlefolk’.

![[The Wasted Years cover thumbnail]](https://v1.jazzbutcher.com/images/releases/fire_wasted_250.jpg)